Guyana’s large stock of natural resources has not only attracted Canadian mining companies, but also waves of unwelcomed corruption. Like much of the continent, this South American country finds its origins and its explosive social-cultural setting throughout years of European colonialism, a bitter past represented by its fractured population and its years of economic strife.

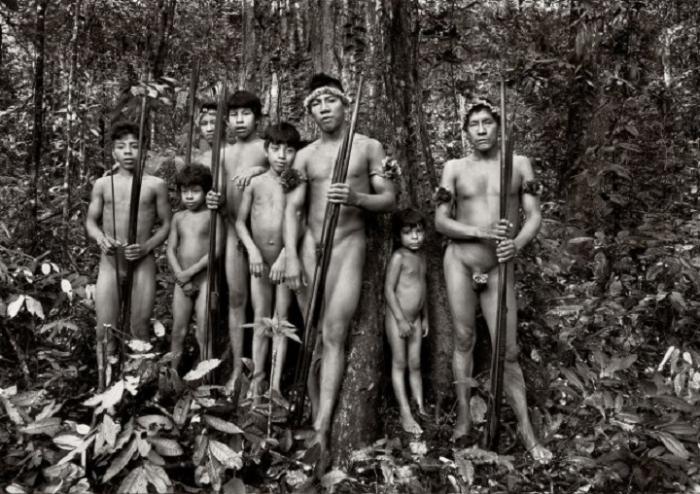

Guyana’s large stock of natural resources has not only attracted Canadian mining companies, but also waves of unwelcomed corruption. Like much of the continent, this South American country finds its origins and its explosive social-cultural setting throughout years of European colonialism, a bitter past represented by its fractured population and its years of economic strife. According to a recent census, 33 percent of Guyana’s population descends from African slaves (brought over by the Dutch), while 50 percent can trace their ancestry to indentured indigenous agricultural workers. [1] This split is still in evidence, where the two main political parties are both ethnically and racially based, causing frequent tension and instability throughout the national government. The continuous hostility among the indigenous Guyanese, often referred to as “Amerindians,” has been historically aggravated by disputes over land titles, lack of empowerment, loss of traditional job skills, and rapidly shifting cultural values. [2] Compounding these problems of ethnic and political divide is the devaluation of what was once the country’s main export crop—sugarcane. The falling price of sugar in recent years has forced Guyana to become more active in investing heavily in extractive industries, such as timber, minerals, and metals. [3]

Regardless of the country’s political instability, foreign corporations have migrated to Guyana, attracted by the country’s vast extractive resource wealth. Among the foreign investors are more than 25 North American companies, seeking to take advantage of Guyana’s mineral wealth, minimal commercial taxes, and decentralized government. The lack of economic regulation has converted Guyana into an international hotspot, as is illustrated by the 17.2 percent national increase in foreign direct investment by 2010. [4] Moreover, one third of this surge in foreign investment was directed towards mining. Of the minerals, gold is the most prized resource and is being heavily extracted by such Canadian firms as Cambior and Guyana Goldfields, Inc. Among Guyana’s leading export goods in 2011, gold accounted for 45 percent of the country’s total export earnings. [5] Furthermore, the current output of gold is expected to increase significantly, particularly due to the developing Guyana Goldfields Aurora project, a massive mine, which once completed, will double the country’s current gold production.

The heavy interest in foreign multinationals is not surprising, as the unstable and corrupt political environment presents an attractive opportunity for foreign firms looking to take advantage of the country’s rotting political and economic institutions. According to Transparency International’s 2011 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), Guyana currently ranks 134 out of 183 countries (with 183 making up the most corrupt mining economy). [6] The majority of this corruption is the product of decades-long economic adversity and strife, as well as institutional weakness, and an ethnically divided society. Recognizing these high vulnerabilities, foreign mining companies (particularly corporations based in Canada) have placed immense pressure on local governments to disregard economic and environmental regulations. The greatest cost created by Guyana’s corruption is evident in the loss of untaxed revenue to foreign corporations, with up to 80 percent of potential gold revenue escaping through the country’s portals. [7] Often these foreign mining corporations use their capital as leverage to take over enormously resource rich, but politically weak states, such as Guyana, to extract all primary products at little or no cost.

Corruption in the mining industry is not simply restricted to Guyana’s borders, but is also present on Canadian soil. As Transparency International’s CPI indicates, Canada’s ranking has dropped from six in 2010 to ten in 2011 (a score of “0” means a country is corruption free), as well as from first to sixth place in another Transparency International survey concerning honesty. [8] The primary causes of this are the many obstacles foreigners face in the Canadian legal system, where it is nearly impossible for foreign citizens to introduce lawsuits involving egregious environmental and human rights violations to Canadian courts. The majority of foreign allegations presented against Canadian companies have been assigned to the host country’s criminal justice system, where they are often prosecuted under much more lenient regulatory standards. For example, in 1997 a lawsuit was filed by villagers against Cambior Corporation regarding the Canadian corporation’s negligence surrounding a dam break disaster along the Omai River. This catastrophe resulted in mass contamination and fatalities. [9] The Quebec court refused to hear the case, claiming it did not have jurisdiction and subsequently passed the lawsuit on to the Guyanese judiciary. The case was then promptly dismissed without any repercussions other than ordering Cambior to pay the villagers’ legal fees. Unfortunately, these fines did not resolve the widespread destruction or necessarily help the Guyana government to implement changes in its economic infrastructure or provide good governance models.

Child labor is also a widespread problem within the Guyanese mining industry. Most recently, an eight-year-old child was found laboring in a gold mine in the Puruni region, near the Venezuelan border. [10] Unfortunately, this shocking case is not unique, as a report issued by the U.S. Department of Labor indicated that more than 44,000 children under the age of 14 are currently working in Guyana (where the legal working age is 15), and many of those under-aged workers can be found in the mines. [11] Compounding this problem further, entire families have been forced to relocate to mining regions in order to find work. These migrations also fuel some of the problems of child labor as many young girls are often forced into prostitution in order to service the mining camps. As the 2011 U.S. Department of Labor report suggests, “Commercial exploitation is a problem in Guyana, including instances of forced prostitution.” This report further explains that there are “girls as young as age 12 working as prostitutes.” [12] Child labor in Guyana is one of the most shocking and abhorrent manifestations of the present Guyanese government’s fundamental lack of commitment to effective law enforcement and industry regulation.

Canadian corporations operating in Guyana have repeatedly demonstrated a total disregard for good governance, human rights and environmental conservation in the small, raffish country. These multinational firms have taken advantage of the absence of governmental oversight of the mining industry, a predatory business practice that has contributed to the rampantly growing problems of child labor and prostitution. The Guyanese government will have to seriously increase the management oversight of its mining and public sectors. It remains to be seen, however, whether it will be able to do this on its own or require assistance from intergovernmental organizations, such as the United Nations or the Inter-American Development Bank. Although heightened supervisory procedures will certainly cause foreign direct investment to decline, they will assure that a greater share of export revenues are likely to be reinvested in the country’s infrastructure, institutions and new investment sources that Guyana desperately needs.

By John Milesi and Kimberly Bullard, Research Associates at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs